AbbVie wins appeal in Humira Patent Thicket Case

- IP News Bulletin

- Aug 8, 2022

- 4 min read

A pair of allegations by welfare-health plans that AbbVie Inc. breached Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Antitrust Act have been overcome once more by the corporation, which holds the patent on the very successful medication Humira. The antitrust case against the drug manufacturer was dismissed on August 1 by the Seventh Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals (Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, et al. v. AbbVie Inc., et al., No. 20-2402, 7th Cir.).

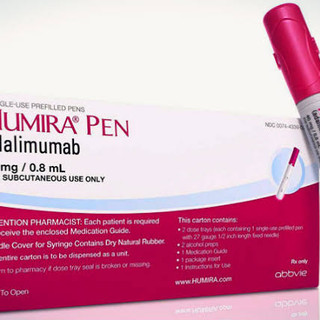

Humira is used to treat a number of conditions including Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, and various types of arthritis. It is listed on the World Health Organization's list of "essential drugs."

The drug's AbbVie patent expired in 2016, but the company still holds 132 other patents covering its production and administration, the last of which doesn't expire until 2034. AbbVie filed a lawsuit based on the additional patents to stop a number of prospective competitors who had been given FDA approval to market a "biosimilar" drug. The patent dispute has since been resolved.

Then, a group of health benefits plans, led by the mayor and city council of Baltimore, filed a lawsuit against AbbVie for its prolific patenting activity, alleging that the company's use of arguably applicable patents to drive away competitors and maintain its monopoly on the Humira market in violation of Section 2 of the Sherman Act, which forbids monopolisation and monopoly maintenance, allowed it to do so.

Furthermore, the welfare plans asserted that the settlement reached by AbbVie with its competitors in the associated patent case was illegal under Section 1 of the Sherman Act, which forbids agreements that unfairly impede trade.

Judge Frank Easterbrook, who authored the ruling for the Seventh Circuit panel, struggled to identify the required anticompetitive behaviour element of a monopolisation claim on the Section 2 claim based on AbbVie's "over-patenting." He said, "The patent laws do not establish a cap on the number of patents any one individual can hold — in general, or pertaining to a single subject." He then queried, "[W]hat's wrong with holding lots of patents?"

The Court stated that the result might have been different had AbbVie defrauded the Patent and Trademark Office, as happened in the Walker Process case.

However, the plaintiffs chose not to rely on the idea of fraudulent petitioning and instead made the "cold" argument that AbbVie's numerous patents were insufficient to uphold AbbVie's monopoly over such a significant medication because they were too "weak."

The court ruled that even dubious patents are lawful. You can dispute with the PTO about whether a patent is "too marginal" to be protected. It "makes it hard to understand how AbbVie may be penalised for its successful petitions to the Patent Office" because the plans did not claim Walker Process fraud. The Noerr-Pennington concept shields valid and effective petitions to the government from antitrust liability, the court said.

Judge Easterbrook noted that "it is possible to use properly issued patents in a way that Noerr-Pennington does not protect," such as asserting "irrelevant patents against producers of biosimilar drugs" "Unsuccessful petitioning can be a source of liability when the petitioner runs up rivals' costs and so stifles competition independent of a petition's success," Judge Easterbrook wrote.

However, the plaintiffs only claimed that AbbVie asserted "some" irrelevant patents against its competitors, not all of them, and the court determined that this was insufficient to qualify as an anticompetitive abuse of process. In any case, the court stated that "the sifting of the wheat from the chaff [that] is a duty for the judges hearing such patent matters" is required to determine the strength or weakness of the patents.

The panel, however, concluded that "a separate antitrust lawsuit brought by parties unrelated to the patent dispute does not justify an attempt to judge by proxy what may have occurred in the patent litigation, but did not."

In their Section 1 claim, the welfare-benefit plans had claimed that the settlement of the patent dispute between AbbVie and possible rivals amounted to a market-allocation arrangement, which the plaintiffs had referred to as a "reverse payment" scheme. The proposals stated that if rival biosimilar producers waited until 2023 to reach the U.S. market, AbbVie would guarantee them more than four years of revenues in Europe.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly stated that regular settlements of patent litigation are legal. If this is a cartel, however, all patent case settlements would be in violation of the Sherman Act, the court ruled.

"AbbVie reached a standard settlement in the United States without paying the contestants, the kind of settlement that [FTC v. Actavis] claims is not problematic. The possible competitors and AbbVie in Europe reached a similar agreement, which is appropriate for the same reason. AbbVie committed to enter before the last patents expired in each [settlement] and didn't pay anyone to delay entry. We interpret the situation in the same way as the district judge.

Lessons can be learned from the case on the significance of evidence that sufficiently allege the essential components of a Section 1 claim (the unlawful agreement) and a monopolisation claim (the anticompetitive activity).

However, one cannot be wholly indifferent to the plaintiffs' attempt to characterise as anticompetitive the results of what is essentially dysfunction at the Patent Office. Both the misuse of the litigation process by wealthy litigants and the manipulation of the patent grant process by patentees to increase the cost of market entrance by competitors are frequent occurrences.

However, it should be clear that anticompetitive outcomes in patent disputes, even when the Patent Office provides assistance, must be investigated and subject to the proper antitrust enforcement.

Comments