Can you trademark "Fuck"?

- IP News Bulletin

- Aug 28, 2022

- 2 min read

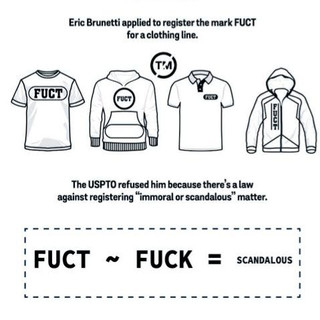

A designer was unsuccessful in getting a more straightforward version of the phrase approved by the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board despite successfully arguing for his "FUCT" trademark at the US Supreme Court and overturning a ban on registering profane trademarks (TTAB).

Because "FUCK" does not serve as a trademark, Erik Brunetti cannot register it for a variety of goods, including jewellery, bags, cell phone cases, and clothing, the TTAB said in a precedent-setting ruling on Monday. It was noted that the word's widespread use was a factor in the decision and that "it now appears without fuss in an impressive breadth of cultural spheres."

Not every designation chosen with the idea of serving a trademark function necessarily succeeds in that goal, the court found in its ruling.

The word is "no ordinary word," according to the board, because of its variety. Beyond sexual activity, it serves as a word intensifier, offends or insults, and expresses melancholy, uncertainty, terror, boredom, irritation, or pleasure.

According to the board, the term is also present on a number of third-party products belonging to pertinent product classifications. According to the report, consumers are more likely to view it as a message or decorative element of the goods than as a maker's mark.

While the Supreme Court heard arguments in his FUCT lawsuit, which stands for "Friends U Can't Trust," Brunetti submitted four applications to register the new mark. Sunglasses, watches, athletic bags, backpacks, wallets, retail services, and online retail platforms would also be covered in the spectrum of goods they would cover.

Due to the length of the term and Brunetti's FUCT appeal, the applications were put on hold while the case was being decided. The examiner took up the FUCK applications after Brunetti persuaded the Supreme Court to determine that the Lanham Act's prohibition on registering obscene marks is unconstitutional and discovered new justifications to deny them—that the word didn't serve as a trademark.

Brunetti claimed that if the examiner just relies on evidence of usage without considering relative frequency, it is impossible to refute a finding that something is "widely used." He provided evidence that allegedly indicated substantially reduced usage over the previous 200 years.

However, the board said that Brunetti's "relative frequency" requirement would be difficult to implement and would not accurately reflect user perception, let alone focus on the application's timing. It stated that "mere commonness" is not a justification for refusal.

The TTAB further stated that the examiner need not demonstrate that customers will not regard a mark as a source-indicator.

It's enough to demonstrate that customers who are accustomed to non-trademark use are unlikely to mistake it for one. It is then up to the applicant to demonstrate otherwise, which Brunetti failed to accomplish, according to the board.

Comments